A Day in the Life of a Montessori Child

What’s it like for an age 3-6 child at Lakeland Montessori Schoolhouse?

by Tim Seldin

President of the Montessori Foundation

Information provided by: www.montessori.org

It is dark at 8:00 on this mid-winter’s morning when Teddy and Jennifer’s mom pulls in to the drop off circle at New Gate. Her two children have been here since each was a toddler. She has made this trip so often over the years that New Gate feels like her second home. She works in town and typically can’t leave work until after 5. Her husband teaches in the local public schools and is off much earlier. He’ll pick the children up from the after school Studio program at 4:30, but if he’s late, he knows that they’ll be fine until he arrives. Many working families appreciate its extended day and summer camp.

Teddy and Jennifer definitely think of New Gate as their second family. Jennifer is one of those children who, after eight years at New Gate, speaks about Montessori with affection and conviction. Visitors often find her coming up without a moment’s hesitation to greet them and offer a cup of coffee or campus tour. When people ask her if she likes it in Montessori, she will smile and say “Sure, how could anyone not love it here. Your teachers are your best friends, the work is really interesting, and the other kids are like my brothers and sisters. Its a family. You feel really close to everyone.”

Jennifer walks Teddy, who’s 4, to his morning supervision room. After dropping him off, she walks into the upper elementary class where she is a 5th grader. She joins two of her friends in the media center, and sits and talks quietly waiting for class to start at 8:30.

Teddy’s morning supervision is in his normal classroom. After hanging up his coat, he walks over to Whelma, the staff member in charge of his room this morning until school officially begins at 9:00. He asks if there is anything ready to eat. Whelma suggests that he help himself. He scoops out a bowl of cereal from a small bin, and adds milk. He takes his morning snack over to a table and eats. Children and their parents drift in to the room every so often, and gradually the number of children in the early morning program grows to about 10.

After eating his breakfast, Teddy meanders over to the easel and begins to paint with Teresa, a little girl just 3 who has only joined the class over the last few weeks. They paint quietly, talking back and forth about nothing in particular. Eventually Teddy tires of painting. He is tempted for a moment just to walk away and leave the easel messy, but he carefully cleans up and away puts his materials.

At 8:30, his teachers arrive, along with several more children. Others follow over the next few minutes until all of the students and the two adults quietly move about the room.

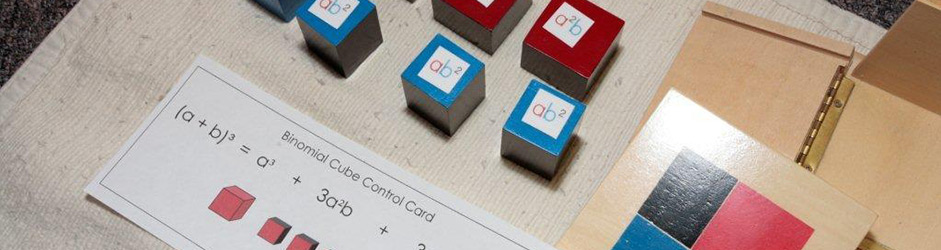

Montessori children work with hands-on learning materials that make abstract concepts clear and concrete. They allow young students to develop a clear inner image of concepts in mathematics, such as how big is a thousand, what we mean when we refer to the ‘hundreds’ column, and what is taking place when we divide one number by another. This approach makes sense to children. Through this foundation of concrete experiential learning, operations in Mathematics, such as addition, become clear and concrete, allowing the child to internalize a clear picture of how the process works.

Teddy and another child have begun to work together to construct and solve a mathematical problem. Using sets of number cards, each decides how many units, tens, hundreds, and thousands will be in his addend. The cards showing the units 1 to 9 are printed in green, the cards showing the numbers from 10 to 90 are printed in blue, the hundreds from 100 to 900 are printed with red ink, and the cards showing the numbers 1000 to 9000 are printed in green again because they represent units of thousands.

“Kids: they dance before they learn

there is anything that isn’t music.”

– William Stafford

As Teddy and his friend construct their numbers, they decide how many units they want, find the card showing that quantity, and place it at the upper right-hand corner of their work space. Next they go to the bank, a central collection of golden bead material, and gather the number of unit beads that corresponds with the number card selected. They repeat this process with the tens, hundreds, and thousands.

The children combine the two addends in the process we call addition. Beginning with the units, the children count the combined quantities to determine the result of adding the two together. When the result is nine or less, they find the large number card that represents the answer. When the addition results in a quantity of ten beads or more, the children stop at the count of ten and carry the ten unit beads to the bank to exchange them for a ten-bar: ten units equals one unit of ten. They repeat this process with the tens, hundreds, and thousands.

It’s about 10 o’clock now, and Teddy is a bit hungry. He wanders over to the snack table and prepares himself several pieces of celery stuffed with peanut butter. He pours himself a cup of apple juice, using a little pitcher that is just right for his small hands. When he is finished, Teddy wipes off his placemat.

Clearing up his snack has put Teddy in the mood to really clean something, and he selects table washing. He gathers a bucket, little pitcher, sponge, scrub brush, towel and soap and proceeds to scrub a small table slowly and methodically. As he works, he is absorbed in the patterns that his brush and sponge made in the soap suds on the table’s surface. Teddy returns everything to its storage place. When he is finished, the table is more or less clean and dry. We have to remember that a four-year-old washes a table for the sheer pleasure of the process; the fact that it might lead to a cleaner surface is incidental. What Teddy is learning above all else is an inner sense of order, a greater sense of independence, and a higher ability to concentrate and follow a complex sequence of steps.

Teddy moves freely around the class, selecting activities that capture his interest. In a very real sense, Teddy and his classmates are responsible for the care of this child-sized environment. When they are hungry, they prepare their own snack and drink. They go to the bathroom without assistance. When something spills, they help one another carefully clean up the mess. We find children cutting raw fruit and vegetables, sweeping, dusting, washing windows. They set tables, tie their own shoes, polish silver, and steadily grow in their self-confidence and independence.

“Children are the living messages

we send to a time we will not see.”

– John W. Whitehead

Noticing that the plants needs watering, Teddy carries the watering can from plant to plant, barely spilling a drop. Now it’s 11 o’clock, and one of his teachers, Mary, comes over and asks him how the morning has been going. They engage in conversation about his latest enthusiasms, which leads Mary to suggest another reading lesson. She and Teddy sit down at a small rug with several wooden tablets on which the shapes of letters are traced in sandpaper. Mary selects a card and slowly traces out the letter d, carefully pronouncing the letter’s phonetic sound: duh, duh, duh. Teddy traces the letter with his tiny hand and repeats the sound made by his teacher.

Teddy doesn’t know this as the letter d yet, and for the next year or so, he will only call it by its phonetic sound: duh. This way, he never needs to learn the familiar process of converting from the letter name, d, to the sound it makes, duh. Continuing on with two or three additional letters, Mary slowly helps Teddy build up a collection of letters which he knows by their phonetic sounds.

Mary leads Teddy through a three-step process. “Teddy, this is duh. Can you say duh? Terrific! Now, this is a buh (the letter b). Teddy, can you show me the duh? Can you give me the buh? Fine. Okay, what is this (holding up one of the sandpaper letters just introduced?” Teddy responds, and the process continues for another few minutes. The entire lesson is fairly brief; perhaps fifteen minutes or so. Before long, Teddy will begin to put sounds together to form simple three-letter words.

Teddy’s day continues just like the morning began. He eats his lunch with the class at 11:45, after which he goes outside with his friends to play. After lunch, the Spanish teacher comes into the room and begins to work with small groups of students. Eventually, she taps Teddy on the shoulder and asks him if he would like to join her for a lesson. He smiles, but graciously declines. He is too engaged in the project that he’s chosen.

In the afternoon he does some more art, listens to selections from a recording of the Nutcracker ballet, works on his shape names with the geometry cabinet, and completes a puzzle map of the United States.

When the day is over, Teddy has probably completed twenty to thirty different activities, most representing curriculum content quite advanced for someone who after all just turned four two months ago. But when his dad picks him up at 4:50, his response to the usual question of “What did you do in school today” is no different from many children, “Oh, I don’t know. I guess I did a lot of stuff!”